Compiled from official National Archive and Service sources, contemporary press reports, personal logbooks, diaries and correspondence, reference books, other sources, and interviews.

Check our Research databases: Database List

.

We seek additional information and photographs. Please contact us via the Helpdesk.

Operation: Essen

Date: 16/17th September 1942 (Wednesday/Thursday)

Unit: 1654 Heavy Conversion Unit (5 Group)

Type: Lancaster I

Serial: W4138

Code: JF-U

Base: RAF Wigsley, Nottinghamshire

Location: Willich, Germany

Pilot: Sgt. Frederick Hope Huntley 777676 RAFVR Age 24. Killed

Fl/Eng: Sgt. Ronald Albert Low 572143 RAF Age 20. Killed

Obs: Fl/Sgt. Leslie Edwin Bell NZ/405364 RNZAF Age 23. Killed

Air/Bmr: Fl/Sgt. John Nelson Secoro King R/75603 RCAF Age 21. Killed

W/Op/Air/Gnr: Sgt. Donald Richard Gilchrist AUS/407641 RAAF Age 29. Killed

Air/Gnr: Fl/Sgt. Stuart Harold Cowley R/109687 RCAF Age 19. Killed

Air/Gnr: Fl/Sgt. Murray Rowe Crocker R/110435 RCAF Age 19. Killed

REASON FOR LOSS:

Taking off from RAF Wigsley in Nottinghamshire to bomb the German city of Essen. Some 369 aircraft taking part from which 41 were lost many to the fierce night fighter attacks but a similar number also taken down by anti-aircraft fire. No night fighter claims have been identified for this loss.

Mr. Donald Gilchrist, nephew of the crew member with the same name, has researched this loss and his is the information that follows. Personal views expressed are those of the compiler. If you wish to use anything from this article Don has requested that you contact him first via our Helpdesk)

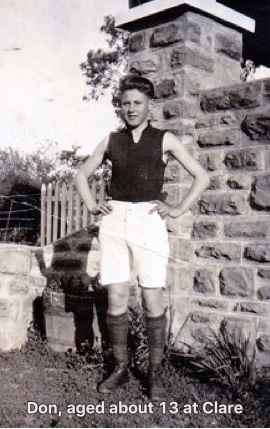

There are two Donald Richard Gilchrists hanging around this story. The first and most important one is the one born on 15th November 1912. He was the middle one of three brothers and it is him that this is really all about so all Dons referred to are him. The second one is me. I am the son of the youngest of those three brothers and I bear the name in honour of that brother. It is a dynastic sounding arrangement but I will get to that in time.

This story has many roots so inevitably some sections are going to appear as asides to the main theme. I do not see any way around that and at the same time cover the tale as completely as I would want but Don’s story is much more than a list of personal events ending on September 16/17th, 1942.

Don’s story is also the story of the cataclysmic events of World War 2 and I chose to relate his part in it including the story of the technology, politics, strategy and tactics of the times as they related to Don’s involvement.

The technology is that of the bombers and their adversaries in the German defence of their military interests. The politics is both internal within the British War Cabinet and externally involving the USA; starting with their chosen role as “The Arsenal of Democracy” and later the role they were forced into as direct combatants, initially in the air with the US 8th Army Air force and then on the ground in western Europe after D-Day, 1944. The strategy is Bomber Command’s role in the overall plan of the British War Cabinet and the tactics were Bomber Command’s unfolding plan to utilise the resources available to them and dealing with the defensive obstacles the Nazis deployed against them.

Right: Pilot, Sgt. Frederick Hope Huntley (courtesy Elaine Hardwick)

The illustrations I selected are a mix of family records and whatever open-source material I could find that was relevant. Where I found material that was directly related to Don’s war I have been as accurate as I can manage but these were turbulent times and many minor inconsistencies between different sources were found that I have smoothed over, whist trying to retain the narrative flow of Don’s involvement, without getting too bogged down in bureaucratic minutiae.

All errors of fact and sequencing are mine alone as I try to record the great enterprise that my uncle took part in and that eventually claimed his life.

Don’s patrilineal line, or the potential for it, stopped sometime on the night of September 16/17th, 1942 in a Lancaster bomber over Essen.

Like almost all aircrew who perished during WW2 he was young. Not as young as some to be sure but as far as the family knew Don had no children and thus no direct descendants. My credentials to write this story begin with my father Stewart Lynn Gilchrist, or Lynn as he preferred to be known. Lynn was the youngest of three brothers born to James Drennan Gilchrist (JD) and Emily Naomi Gilchrist (née Bowley), known as “Em”, in the Clare Valley, in the mid-north of South Australia. The eldest brother, Robert John (Bob) was a fair bit older than Don and was of a bookish disposition and although he was recorded as Don’s ‘Next of Kin’ he takes little further active part in this tale other than as the recipient of Don’s personal effects after he was killed in action.

Right: JD as a young man and Em somewhat later in life. JD took over the family business on the death of his father and I believe JD was only in his twenties when this happened. These photos are courtesy of the Clare Historical Society and they are undated.

Right: JD as a young man and Em somewhat later in life. JD took over the family business on the death of his father and I believe JD was only in his twenties when this happened. These photos are courtesy of the Clare Historical Society and they are undated.

Of the 3 brothers Don and Lynn were the closest and Don used to refer to my father affectionately as “young un”. When Don was killed in one of the many air battles fought over the Ruhr Valley during WW2 Lynn was already an NCO in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF). He had joined up in 1938 rising rapidly in rank to Gunnery Sergeant in 1 Heavy Brigade, Royal Australian Artillery, and was keen to join the fight. Perhaps seeking the approval of his idolised big brother. The news of Don’s death must have come as a great shock. He never spoke of his emotions at the time but the fact that he named his first son after his closest brother speaks volumes for the depth of his feelings for Don.

Had Don survived the war and started a family his children would have been his chroniclers instead of me, but that is not how things turned out. Don was a bit of a lad and had lived a very full bachelor’s life until his death. There may even be biological offspring out there but as far as I know I am the closest living relative that he has and with the recent 100th anniversary of the disastrous Gallipoli landings; if not now, when? And if not me, then who?

Early days:

Don had followed his father into his grandfather’s business, that of bespoke tailor, which was started in Clare in about 1890. Not that there was any other kind of clothing for genteel country folk in the late 1920s. Don’s grandfather and his family were in a group of six families who had privately chartered a ship and emigrated from Renfrew, just west of Glasgow, to escape, with active encouragement from the UK Foreign Office, to a better life in the Southern Hemisphere. Initially the group landed in Montevideo in Uruguay and went up the Rio de la Plata and Rio Paraguay to check it out.

In the late 19th century there were several attempts by citizens of the British Empire to start ideologically based settlements in South America. English settlers went to Nueva Londres and Australian agrarian socialists (19th century Hippies) started Nueva Australia in 1893. Perhaps it is these groups that Don’s grandparents intended to join. But like most communes the dictatorial control of the early leaders fomented discontent in the ranks within a few generations and most, but not all, of such idealistically based enterprises fail miserably within a few generations.

The independent Gilchrists and Drennans found the conditions not to their liking and they re-embarked, landing finally in South Australia. An interesting story in itself I am sure, but one I have not researched and peripheral to Don’s story in any case.

Both Don and his younger brother did their apprenticeships with their father at “J. D. Gilchrist and Sons, Tailors”, in the main street of Clare, in which building a menswear shop still operated in 2009 by the family that bought the business after J.D’s death.

The family home was a fine stone structure looking out over Clare across the Hutt River that flows through the town. I took this photo in 2009 and the present owners were kind enough to show me over it and I was able to identify the room occupied by Don and my father.

Below is the shopfront on the main street of Clare as I found it in 2009. When I was there previously in the 1980s, behind the current sheet metal of the facade was: “JD Gilchrist & Sons. Tailors” embossed in stone.

Eventually Don started a tailoring business about 50 kms down the road at Riverton; although whether as a branch of JD’s business or in his own right I do not know. As to its success or not I do not know but the trophies for tennis and golf continued to roll in. Dad thought that Don saw WW2 as a natural extension of competitive sport; but for whatever reason Don enlisted in the RAAF on June 14th, 1940. On his application, in the section “sports and games”, he listed: “All sports, preferably football, golf, tennis.”

I can understand why he did not try the Navy, being a boy from the bush and all, but it beats me why he chose the Air Force over the Army. I think any of the services would have been very agreeably disposed to him with his athletic prowess and competitive nature. Perhaps size had something to do with it. At 5’7” (170cm) Don was not a tall man. Any altitude in the family after that, and there is plenty, must have come from the other side of the family.

Training:

He formally applied for enlisting and training as: Pilot, Air Observer or Air Gunner in the RAAF on 14th June, 1940 and signed up for the duration of the war and 12 months after. Even in 1940 the RAAF seemed in no doubt as to the ultimate outcome.

His first posting was to No 1 ITS (Initial Training School) at Somers in Victoria in December 1940 and then to No 1 WAGS (Wireless and Air Gunners School) at Ballarat on 6th February 1941 and eventually course No 10 at 2 BAGS (Bombardier Air Gunners School) located at Port Pirie in South Australia on 26th July 1941. This final posting ended his contact with the Empire Air Training Scheme (EATS) and from this he was made Temporary Sergeant W/O/Air/Gnr and listed for posting to the RAF in the UK. The EATS was formed early in the war, and disbanded toward the end of it as the outcome became clear. It was a very diverse organisation created to supply aircrew to the expanding air war over the industrial heartland of Germany and there were sections of it all over Australia as well as South Africa and a very large Canadian effort.

The story in the family is that Don was in Adelaide for some reason and went to the beach at Glenelg to round up some girls for a party. One of those girls was Gwen Good, ultimately to become my mother, who was a milliner (ladies hat maker) at the John Martins store on Rundle Street in the city. At this party she met my father Lynn, who was on leave at the time from his unit 1 Heavy Brigade, Royal Australian Artillery which was stationed at North Head, Sydney.

By mid 1941 both JD and Em had died. JD as a result of a fall from a horse while hunting and a subsequent stroke, or the other way round. He was a prominent member of the Clare Valley community.

JD Gilchrist and sons was the largest employer in the area and in 1915-1917 he was Mayor of Clare. Less than a year after JD died Em was dead too. Her death certificate records “Melancholia” as the cause of death so it gives credence to Lynn’s idea that she just died of a broken heart. One thing is for sure and that is that JD was a dominating figure, at home as well as about the town, and with him gone perhaps there did not seem much point in her hanging around.

JD was fiercely religious and was very prominent in the Presbyterian Church being an Elder, lay preacher and loyal financial supporter. Bob, the eldest son, retained a bit of that religiosity but certainly my father did not, nor did I ever get the impression that Don followed in his father’s ecclesiastical inclinations. Both JD and Em were buried in Clare cemetery with much ceremony but by this time Bob was advancing his career as a teacher in Adelaide, Lynn was away on military service and Don was in Victoria early on in his training with the RAAF.

On a visit in 2009 I found no physical evidence of their graves. I have a photograph of one of the graves, courtesy of The Clare Historical Society and cemetery records give a location and indicate that the two were side by side but not enough remained for me to pinpoint them with any certainty.

This photo (left), taken by my father, shows Don at the back and Gwen, my mother, in front to the left. This picture is labelled “Easter 1940” and is taken outside the family home. At this stage both JD and Em were still alive but this may well have been the last time Don or my father saw them. At the time Lynn was an NCO in the army, 1 Heavy Brigade, Royal Australian Artillery, serving at North Head in Sydney. My parents were married in Sydney after this photo was taken.

Because of the photographs of Lynn and Gwen together with Don and an un-named lady at Clare at Easter 1940 (March) my best estimate is that sometime before Easter 1940 Lynn met Gwen at a party organised by Don.

By some accounts Don thought Gwen a bit of a tart and warned Lynn of the risks of marrying her but whether in jealousy or criticism is hard to say. I am rather of the opinion it was more of a statement made in envy of his young brother because she was a very nice looking lady. Tall and statuesque she would have towered over Don and if he ever said words to that effect then he was probably covetously teasing his younger brother. This photo was in dad’s possession during their courtship. Gwen is fooling around with some seaweed on the beach at Port Noarlunga, south of Adelaide while dad was gunnery sergeant, serving with 1 Hvy Bde RAA at North Head in Sydney.

One thing is for sure; that Don himself had no objection to a few available and presentable ladies around him. By the time we see a few photographs of them all together at a John Martins staff party they are all very happy in each others company. The party in question must have coincided with Dons pre-embarkation leave as Don is in uniform with rank and his aircrew wings and Lynn is in uniform as an NCO in the Royal Australian Artillery with Gwen squeezed happily between the two brothers.

The standard route for Australian aircrew being posted to RAAF units in England was by ship from Sydney to San Francisco, then train to New York via Chicago and then by ship across the Atlantic to England.

Don departed from Sydney on 18th September 1941 crossing the Pacific by ship to the USA. I have photos of him and other aircrew with a couple of girls in California (below left) and him, again with a girl, a Miss Moeden, “outside Simpson’s Store” in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada in October 1941 (below right).

The left hand photo above was with Don’s personal possessions and unlabelled. The three sergeants behind all wear AG wings and I can only presume they were colleagues of Don’s from his training. The photo records the names of both of the ladies and an address indicates that it was taken in California and obviously aboard a ship of some sort. Don is in the middle of the lower row with a girl on his knee and the sergeant to the right wears pilot’s wings but apart from recognising Don I know nothing about the others.

He arrived in the UK on November 4th 1941, a week short of his 29th birthday and, according to his service record, was immediately posted to 25 Operational Training Unit (OTU) at RAF Yatesbury. The photo left is labelled: “12th floor Marine Court. Esplanade. Hastings Sussex. Smithy and self keeping close to the sun during its annual 5 min appearance.” I do not know who “Smithy” was but he bears a great resemblance to the Sergeant, top left, in the picture with the 2 ladies taken in California.

Postings in the RAF:

25 OTU RAF is listed as a squadron (identifying letters PP) and was re-equipped with Vickers Wellington Ic’s in April 1942. It was based at RAF Finningley, carrying out training and Operations with 7 Group, Bomber Command. During the early war years Yatesbury was the location of all advanced radar and radio communication training. It seems that by now Don’s role was expanded to include Radio Operator as well as involvement in Bomb Aiming and Aerial Gunnery. So it is probable that that after initial radio training at Yatesbury , Wiltshire, Don went to 25 OTU at Finningley, South Yorkshire.

25 OTU was formed and renamed from: “C” Flight, 106 Squadron, which used Avro Ansons and Handley Page Hampdens before moving on to more modern operational types like Vickers Wellingtons as shown. It provided crews for operations with Bomber Command, losing 4 Hampdens and 9 Wellingtons on Operations during the first half of 1942. One of the major operations mounted was taking part in the first “1000 Bomber” raid on Cologne on May 30/31, 1942 where the unit lost 1 Wellington. (Wellington L7802) The crew all survived as PoW’s, baling out after the aircraft sustained damage over the target. At the time as pictured above RAF Finningley used grass runways only being upgraded to concrete class A standard in late 1943 / early 1944 after 25 OTU had been disbanded.

Family research:

For years, as I was trying to pick Lynn’s brains for information as to family events and history, there was talk of a mythical photo of Don standing under the wing of a Lancaster bomber. Look as I might through mum and dad’s photos I had never come across it and I began to think I never would. Here the story has to digress a bit and bring Don’s older brother Bob in.

In the mid 1990s when my wife Robyn and I were back in Australia for a while between legs of our voyage around the world in “Stylopora” and we were in Adelaide catching up with the kids. We happened to be going for a drive down the south coast and decided to pay an unannounced visit to see Bob and Esma at Maslin Beach where they lived in retirement. We found them at home and in the course of conversation Don’s service came up and Bob took me into his study and showed me a note-book of Don’s that, in a personal diary kind of way, recorded his time in the UK from his first posting to operational squadron duties until his death. We agreed that ultimately I should come into possession of all stuff related to Don’s war service but that for now it should stay with Bob as our life was too uncertain to offer any security for irreplaceable family treasures.

As it turned out Bob died before we saw him again and all of his personal papers went to his daughter Jenny where they sat for a long time. Jen and I had always been close and we stayed in contact while Rob and I continued on our circumnavigation. She assured me that when she got around to going through Bob’s stuff that she would send anything related to Don up to me when we got back and were settled in Cairns. I was already in possession of Dons war medals and the originals of War Office notification of his death.

Early in 2015 the stuff turned up and it is a treasure trove of family memorabilia. The arrival of Don’s stuff is what galvanised me into activity regarding Don’s wartime service. That and a lot of Anzac tradition activity related to the one hundred year anniversary of the Gallipoli landings made me determined to get all of Don’s stuff together and compile it into a reasonable form. That effort has taken on a life of its own and periodically occupies me still. Every time I think it is complete I stumble on something else which requires insertion and, like Topsy, Don’s story grows. Just recently I went back into my library to look at a volume entitled “Royal Air Force at War: The unseen films”. One of those short films is called “Sky Giant” and it was Movie-tone’s celebration of the arrival of Lancasters into front line squadrons. Watching it armed with Dons diary it was revealed that the film was shot at RAF Scampton and most of the footage is of 83 squadron aircraft and it was made just after Don arrived at 83 Squadron. It left me with a strange feeling realising that Don could have been flying in the aircraft featured or in the briefing room scenes of the film.

The two most important pieces for me were his diary and a collection of photos one of which was the mythical photo of Don standing under the wing of a bomber but it was a Vickers Wellington Ic not a Lancaster.

The photo is tiny and consequently a bit blurry and the squadron insignia on the nose of the Wellington cannot be seen with any clarity but such adornments were common on Wellingtons, particularly those assigned to Operational Training Unit duties.

The photo is unlabelled and shows Don, on the left, and a colleague standing near the port motor of a Vickers Wellington Ic parked on the grass. It took a great deal of research of RAF records to work out that the photo was most likely taken at 25 Operational Training Unit at RAF Finningley sometime between late March 1942 and Don’s posting to operations at 83 Squadron flying out of RAF Scampton in Lincolnshire on 16th June 1942. RAF records are difficult to pin down at this hectic time.

Don’s service record clearly shows him posted to “25 OTU at Yatesbury” upon his arrival in the UK. But Yatesbury and Finningly are not even in the same county. It is likely that the posting to 25 OTU at Yatesbury was a composite entry in his record of service that encompassed a short posting to the radio school whilst in transit to the OTU at RAF Finningley which by this stage was re-equipped with Wellington Ic’s such as the one pictured. RAF Yatesbury was basically a ground school for radio and radar with no record of operational aircraft types assigned. 25 OTU was formed in March 1941 at RAF Finningley to train night bomber crews for squadrons operating Handley Page Hampdens. 25 OTU was fully re-equipped with Wellington Ic’s for squadron duties by April 1942. It is never recorded as being based at, or assigned to, the Radio Training School at Yatesbury.

RAF unit histories record that during 1942, 25 OTU provided crews for a number of operations and the unit was certainly involved in the first “1,000 bomber” raid on Cologne on 30/31st May 1942. Don would have been at 25 OTU and well advanced in his operational training so he could have been involved. The unit disbanded in February 1943.

From Yatesbury and Finningley Don was posted to B Flight, 83 Squadron at RAF Scampton, joining the squadron for operational duties on 17th June, 1942. This was a time of great expansion for Bomber Command. The dynamic Air Marshall, Sir Arthur Harris had taken command in early 1942. Harris had big plans and things were really starting to crank up.

But now it is time to step aside from Don for a while as it is necessary to explore the times, technology and the machine that was to have such a bearing on Don’s life and WW2 in general.

Bombing in the early war years:

In this day and age, when even your mobile phone will tell you where you are to a few centimetres accuracy almost anywhere on the planet, it is difficult to appreciate the huge problems that existed in 1942 for aircrew in establishing their location with anything like military accuracy. In the urgency of war everything was cobbled together with little opportunity for testing and refinement. For example the Battle of Britain was fought using radars developed using magnetron valves from surgical diathermy units. They literally went to the hospitals and nicked the parts that they needed from the diathermy machines in the operating theatres. Without them they would never have had sufficient advance warning of where and when the Luftwaffe air fleets from German occupied France were going to attack. Without them a good case can be made that Operation Sea Lion (Hitler’s invasion plan for England in summer 1940) would have been successfully mounted and the war could have been over by Christmas 1940 as the Nazis occupied the UK and a very different world to the one we enjoy would likely have eventuated.

In 1941 and 42 navigational Radars did not exist. H2S, a form of ground scanning radar came along in 1943 and even then it was tricky to use and only selected aircraft were fitted with it. Other aids like Gee and Oboe arrived in late 1943 but these being VHF transmissions were limited to line of sight and thus limited to the altitude of the receiver PFF aircraft and never even extended as far as Berlin at wars end.

Radar of any kind was an invitation to trouble as German night fighters soon learned to home in on the signals emitted from RAF aircraft and once engaged the crew of an RAF heavy bomber laden with high octane fuel and high explosive had little chance of survival.

In 1942 all navigators had was Deduced (Ded) Reckoning (DR) and for that they had to know the wind at their altitude along the route to the target. Meteorology was a science in 1940 but only an infant one and the boffins had very little in the way of accuracy to estimate what the wind might be, in strength or direction, at the operational altitude of a Lancaster bomber (23,000 ft) flying many hundreds of miles over occupied territory toward the target. Weather was usually cloudy, often filthy and the ground all over the UK and Western Europe was usually covered in industrial haze and blacked out anyway. The best that they could do in 1942, as the Bomber Command effort intensified, was to start with their best guess and rely on the first few aircraft of the bomber stream learning the reality of the “Met Wind” along their track from direct observation of ground features below.

Ded-reckoning told them where they thought they should be; direct observation told them where they actually were and the difference between the two positions allowed the navigator to put a value on the true “Met wind”. This information would be encoded on the aircraft and radioed back to Bomber Command HQ who would then factor it in to the navigation section of the battle plan for that night, re-code it and re-transmit the new information and navigational corrections to all aircraft in the bomber stream. Anyone with High Frequency, 2-way radio experience will know that, even now, long-range wireless telephony is a chancy business and it was far more primitive in 1942. For all the limitations of the technology of the day its encoded transmissions were vital to the success, or otherwise, of that nights mission. If they didn’t do it right when they were already halfway there they would only have to keep going back, and dying in the process, until they did get it right.

In the bombers the wireless operator (W/Op) would de-code it and pass it to the navigator who would then calculate appropriate course corrections and pass them to the pilot. For this reason the W/Op, navigator and pilot were all very close together, their common purpose being to put the aircraft and its bomb load over the target with precision so that the whole trip was not a complete waste of time in those dark and hostile skies over Germany during WW2.

Until Harris arrived Bomber Commands results had been largely ineffectual. It may have been a bit of a morale boost for the long suffering people of the UK after many early setbacks and enduring the London Blitz but it wasn’t doing much to end the war. Photographic reconnaissance of the early efforts to bomb enemy targets at night had presented a pretty dismal picture. Only about one in five aircraft were bombing within 5 miles of their designated aiming point. Bomber Command had switched to night operations in the harsh light of the losses, up to 30%, they were suffering during daylight raids with no fighter escort against well defended targets.

The politics of US involvement in Europe:

The reality was at this stage of the war the only theatre that Britain could operate in offensively was the air. And the UK had to survive in the fight long enough to get the USA into the war. With France fallen and occupied by the Nazis, Churchill knew US involvement was the only way for the western democracies to win the war and avoid a repeat of the carnage of the Western Front in WW1. On the other side of the Atlantic, in the USA, President Roosevelt was favourably disposed personally toward the ultimate success of the western democracies both on a philosophical and a practical level with Roosevelt’s “Arsenal of Democracy” policy but others in the US Administration did not feel the domestic political climate was ready at that time for direct, “boots on the ground”, involvement in the war in Europe.

Early on in the war Roosevelt had dispatched several private emissaries including Harry Hopkins and Averell Harriman to assess the level of resolve in the British people to stand up to the Nazis. He did not trust his senior diplomats in England, particularly US Ambassador Joe Kennedy, who was a known German sympathiser.

Late in his mission to Britain the reclusive and taciturn Hopkins was asked to address a dinner at Oxford at which Churchill was present. Hopkins famously quoted the Bible as his only response saying:

“Whither thou goest I will go, and whither thou lodgest I will lodge. Thy people shall be my people, and thy God my God. Even to the end.”

Churchill was said to have been moved to tears.

Japan solved the dilemma for both Churchill and the Americans on December 7th, 1941.

Tactical developments:

Back in the UK there were major developments in Bomber Command. The best solution for the RAF’s dilemma of not knowing where the hell they were when they dropped their bombs was to create a specialised force of bombers who would mark the turning points on the route that the main force of bombers would take with high altitude flares and also mark the target with distinctive, bright coloured flares on the ground. This would be called the “Path Finder Force” (PFF) and to man it they chose the most experienced crews and squadrons from Bomber Command to fill it. Bomber Commands new policy was “Area Bombing” designed to smash the ability of the German Military Industrial Complex to produce the wherewithal to conduct advanced warfare and destroy the morale of the German population at large to continue the war. The aircraft that the new battle plan was to be based around was the new Avro Lancaster heavy bomber.

The instruments of policy:

The chief designer at A. V. Roe and co. (Avro), Roy Chadwick, knew a dog when he saw one and, in November 1936, perusing the contradictory and disorganised Air Ministry Spec 13/36 for a “high performance twin engine bomber with torpedo bombing capacity” he knew he was looking at one then. “High performance”, 8,000 lb bomb-load, 2 engines of unproven design… “No” he thought, “Too complex, doesn’t really know what it wants to do, not enough power even if the engines work and too slow anyway.” The limitations of Spec 13/36 percolated in the back of his mind as he worked on Avro’s response to the Air Ministry’ invitation to tender for the order.

Perhaps to his great surprise Avro got the nod to build the aircraft envisaged by Spec 13/36. The bastard child of this ministerial bright idea was the Avro Manchester and the wonder engine to propel the beast was the Rolls Royce (RR) Vulture, still in a very early developmental stage. In order to cram more power into the minimum nose profile for less air resistance meant that cylinders had to be put all round the propeller shaft in a more efficient way than the current state of the art exemplified by the Rolls Royce Merlin and German Daimler Benz DB 601; these V 12 designs had topped out at about 1,300 hp by 1941. RR proposed to take an established V 12 Peregrine engine and then graft it to another Peregrine inverted underneath, all connected to a common crankshaft making an X 24 of about 1,850 hp.

The aircraft pictured left is a Manchester 1of 83 Squadron flying out of RAF Scampton. When her squadron identification OL-Q was transferred to a new Lancaster 1 at 83 Squadron on 29th June 1942 that aircraft went on to the most celebrated career of any Lancaster ever built and the history of that aeroplane, R5868, as “Q-Queenie”, overlapped with Don’s story.

This is Don’s story more than Roy Chadwick’s so as much as I would like to I will not go into too much detail but the idea behind Spec 13/36 never worked. The power was never there and the engines were very unreliable, suffering chronic overheating and tending to break con-rods thereby destroying themselves while running in flight. The Manchester could hold altitude on one engine in flight testing but flying around hostile night skies, struggling to keep in the air on one engine with a full operational load of bombs and fuel while a good proportion of the German military were doing their best to kill them was not an ideal survival scenario for the aircraft or the crew.

The only engine available at the time with the combination of reliability and power that Chadwick knew he would need was Rolls Royce’s V 12 Merlin engine but they were in very short supply and Chadwick’s forming idea would need four of them. Everybody was clamouring for them as they were fitted to aircraft already in full production like the Spitfire, Hurricane and Mosquito. But his window of opportunity was small and if he didn’t get his hands on some engines soon Chadwick knew that his idea to transform the Manchester into something effective would be stillborn and he would find himself out of a job as an aeroplane designer. About this time, against Rolls Royce’s wishes, because the demand for Merlins was so great, the Air Ministry decreed that the Packard Corporation would build Merlins under license in the US and this eased the supply issue somewhat. The engines that Packard built were fully interchangeable with those of Rolls Royce and went on to power all types that used Merlins including Lancasters built under license in Canada and the famous P-51 Mustang.

As he watched the teething problems of the Vulture Chadwick’s ideas had crystallised. He was now working on a modification of the basic Manchester airframe to accommodate 4 Merlins on an extended wing, a wider tail plane and taller tail fins to solve some lateral stability problems with the Manchester and he became progressively more convinced that he was really on to something. The simplicity of the tooling design made the changes envisioned an easy proposition. Chadwick’s design ethos was simplicity. Make it easy to build, use proven engines and design it to carry bombs that haven’t even been thought of yet. “When they come to their senses” he must have thought as he doodled away with his idea, “this is what they will want.”

In some ways Chadwick was left holding the baby. Early in the tendering process for spec 13/36 Handley Page, the other manufacturer had decided that no matter how the Vulture turned out it would not have enough power for their rather overweight design so they dropped out and left Avro and the Air Ministry to fight it out. While Avro toiled with Spec 13/36 Handley Page got on with satisfying the earlier Air Ministry Spec12/36 for a 4 motor heavy bomber. Handley Page’s design, eventually to become the Halifax, got a head start and by the time Avro and the Air Ministry realised they were both wasting their time Handley Page had a good lead.

For a while it looked like the entire Manchester plan was to be prematurely scrapped due to heavy operational and training losses after only 200 of an initial order of 1200 aircraft were delivered. The whole Avro factory was then to be given over to produce the Handley Page Halifax.

But Chadwick true to his Avro roots would have none of that. His ‘old boy’ network had him very chummy with the chairman of Rolls Royce and he quietly had himself shipped 4 Merlins straight off the production line and in the unheard of time frame of 6 months had an airworthy example of his bright idea.

Avro called it Type 683 and from its first flight everybody knew the aircraft was a winner. It was fast, looked great, flew like a pilots dream and could carry incredible loads. The performance was so outstanding that everyone was a bit non-plussed as to where this miraculous transformation from that of the troubled and disappointing Manchester had come from.

When first flown by test pilots at the RAF experimental facility at Boscombe Down the Lancaster was immediately assessed as “Eminently suitable for operational duties.” When the test pilots at Boscombe Down were unimpressed they were not backward in making their opinion known. Reporting on one type they summed up saying; “Gaining entry into this aircraft is difficult. It ought to be made impossible!”

A Lancaster 3 of 61 Squadron shows the cavernous bomb bay that allowed the Lancaster to carry the largest weapons (like Cookies, Tallboy and Grand Slam) of any bomber type during WW2.

This is a common bombload for a Lancaster. A 4,000lb “Cookie” surrounded by 30lb incendiaries totalling 14,000lb. The armourers give some some sort of scale to the bomb-bay but at the same time obscure the back half.

The “Cookie” was placed right in the middle. The bomb load could vary a great deal. Pathfinder aircraft often carried only high altitude routing flares or coloured ground markers for the target. Surrounding the Cookie could be 30lb incendiaries, 4 lb incendiaries or a variety of medium case high explosive bombs from 250lb to 1000lb with contact or time delay fusing.

High over Germany on a daylight raid over Duisberg, October 14th, 1944, Lancaster 1, SR-B (NG128), flown by F/O. R.B.Tibbs of 101 Squadron, releases its bomb load of a 4,000lb Cookie and 30lb incendiaries. Forward of mid/upper turret are 2 x “Air Borne Cigar” radar jamming antennas.

This particular raid in 1944 was part of Operation Hurricane, a joint operation involving three coordinated attacks. Bomber Command attacked in strength during daylight on October 14th, as pictured above, with 1,013 aircraft, including 519 Lancasters, dropping 3,574 tons of HE and 820 tons of incendiaries with RAF fighter escort, and later the same day the US 8th AAF despatched 1,251 heavy bombers escorted by 749 fighters to Cologne. On the night of 14/15th the RAF went back to Duisberg with 941 heavies after target marking by 39 Mosquitoes, dropped 4,040 tons of high explosive and 500 tons of incendiaries. Fighter losses are not recorded but total bombers sorties were 3,174 and 26 losses giving total losses of 0.82%. By this stage of the war operational losses by bombers was relatively low by the standards of 1942 and 43.

In one sense the Spec 13/36 came up trumps because of the torpedo requirement. At more than 18 feet long and nearly 2 feet in diameter. A standard torpedo in the Navy arsenal was more than any aircraft then flying could accommodate within an internal bomb-bay. A Lancaster’s bomb bay stretched from underneath the pilot’s seat back, underneath the main-spar to below the mid-upper gunner’s turret. A senior US Air Force general visiting an RAF station early in the war was heard to exclaim “Jesus! This kite is all bomb-bay.”

In the end the peculiarity of Spec 13/36 enabled the Lancaster to unfetter the designers of bombs and accommodate the biggest bombs that were developed by any combatant during the second world war. These included the bouncing bomb that burst the Ruhr dams in 1943, the 4,000lb Cookie and other “Blockbuster” designs weighing 8,000lb and 12,000lb “Super blockbusters”, the “earthquake” bombs of Barnes Wallis; 14,000lb Tallboy and the gigantic 22,000lb Grand Slam. These put the Lancaster in a class of its own and the Go-To machine when it came to original bomb designs for specific target types like dams, canals, viaducts, massively reinforced submarine pens and battleships.

The realities of the bombers war over Europe:

There were fundamental differences between British and US bombing tactics which persevered throughout the war. They started out the same with daylight attacks on purely military targets but horrendous losses in 1940 and 1941 caused the RAF to change their approach. They shifted to night bombing and immediately came up against the problem of: Where the hell am I and where is the target? The brutal reality was that for the duration of the war, at least until late 1944, the only things that the RAAF could reliably find at night were big cities and out of this came the “Area Bombing” strategy. The aim was to disrupt wartime industry by flattening large areas of industrial cities and the accommodations of the workers in those factories were legitimately part of that plan.

The main defence of the British aircraft was stealth under cover of darkness with massed aircraft and, when under attack, manoeuvrability. The gunners main job was observation for night-fighter threats and if the guns had a role it was to keep the fighters back to increase the range which limited the effectiveness of the German cannon and call the evasive action to the pilot.

In daylight the US 8th AAF relied on groups of heavily armed bombers in close formation defending themselves. B17s and B24s had 6 gunners, or more, manning heavy 50 calibre machine guns but they suffered huge losses in late 1942 and 1943. In one battle over the ball bearing factory at Scweinfurt in October 1943 fully 198 US aircraft out of 291 involved were either damaged or destroyed and it was not until the arrival of long-range fighter escorts (P-47 and P-51) in February 1944 together with a battle plan that allowed the bombers to have relays of fighter escorts all the way to the target and back that their loss rate became manageable. Harris considered the US loss rate to be the natural consequence of daylight operations.

This photograph of a formation of B 17 “Flying Fortresses” gives an idea of the density of aircraft that the US 8th AAF considered appropriate for heavy bomber formations to defend themselves during unescorted daylight raids over Western Europe.

The photo above left shows the defensive armament on a B 24 Liberator. All 6 gunners used 50 cal heavy machine guns and, occasionally, an extra 2 gunners were carried forward of the cockpit, one on each side behind the forward twin 50 turret. Even with this firepower the American losses became rapidly unsustainable, galvanising the development of long-range fighter escort aircraft such as the British commissioned, largely designed and Rolls Royce engined, but American built, P-51B and D Mustang (shown). While the Mustang was the pre-eminent escort; purely American P-47 Thunderbolt and twin engine P-38 Lightnings were also extensively used.

The British did everything to maximise the bomb load so night operations, condensed bomber streams and evasive action became their preferred approach. The USAAF tactics evolved to daylight precision raids conducted by tight formations of heavily armed bombers with close fighter escort but carrying relatively light bomb loads compared to the RAF.

To put the load carrying capacity of the Lancaster into perspective; the equivalent air craft in the US 8th Army Air Force during their daylight operations over Germany were the B-17 Flying Fortress which could carry 4,500 lb, albeit to a somewhat higher altitude. And the B-24 Liberator could get 5000 lb of bombs to about the same height and operational range as a Lancaster.

The ‘standard” load for a Lancaster was 14,000 lb at 23,000 feet and at the end of the war the Lancaster carried the 22,000 lb Grand Slam into action, all 10 tons of it. Interestingly Grand Slam was designed by Barnes Wallace, the same genius that came up with the ‘bouncing’, bomb (code named Upkeep) that was used on operation ‘Chastise’ when Lancasters of 617 Squadron burst the major dams serving the steel works of the Ruhr valley on the night of 16/17th May 1943; the famous “Dambusters” raid. It must be said though that the Lanc could only get Grand Slam to 18,000 ft and not its design release height of 24,000 ft in order for the bomb to go supersonic as it was intended to do.

A Lancaster 3 of 617 Squadron releases a 22,000lb ‘Grand Slam’ in a raid on the Arnsberg Viaduct on 15th March 1945. This bomb type was the largest dropped by any aircraft in WW2. The bomb was heavily armoured and was designed to penetrate deep underground before detonating and destroying its target by creating a local earthquake which shook it to bits. This type had a smaller (14000lb) brother called ‘Tallboy’ which operated on the same principle and was the type used when 617 squadron sank the German battleship Tirpitz in Tromso Fijord on 12th November, 1944. Notice the absence of the mid-upper turret and bomb-bay doors. Even a Lancaster’s enormous bomb-bay could not fully accommodate ‘Grand Slam’.

In an RAF bomb dump at Woodhall Spa a 10 ton “Grand Slam” dwarfs the armourers.

The area around the Bielefeld Viaduct is pock marked by the many craters of previous unsuccessful attacks. Grand Slam was not intended to hit the target but rather arrive as a near miss, penetrate deep underground before exploding creating a local earthquake which then shook the target to bits. This was a vital route for German reinforcements to get to battlefields after the Normandy invasion by the allies on D-Day, 1944.

This is the concrete reinforced roof of the U-Boat pens in Farge near Bremen. Similar facilities at Brest and Le Havre in occupied France were also attacked. The proximity of these safe havens for the U-Boat “Wolf Packs” to the areas where they attacked the Allied convoys during the Battle of the Atlantic was vital. Barnes Wallis’s Tallboy and Grand Slam were the only weapons that could successfully attack these targets and Lancaster was the only aircraft that could carry them.

Harris was determined to bomb Germany out of the war and after the area bombing of London, Coventry and other UK cities by the Nazis there was enormous popular support for his tactics. Harris brutally summed up the popular mood in his famous speech finishing:

“Germany sowed the wind and now they are going to reap the whirlwind.”

To put his plan into action he needed a supreme bomb carrying instrument and the Avro Lancaster was that instrument.

Avro Lancaster:

So immediately successful was the Lancaster that the production line for Manchester’s was simply re-tooled to build Lancasters. Part of Chadwick’s genius was to create the Lancaster from all the good bits of the Manchester airframe. All they had to do was build an extra jig for the new inner wing section, stiffen up the main spar for the extra load capacity and solve the lateral stability issue by widening the tail section between the 2 rudders. All Manchester’s that were currently on the production line were simply turned into Lancasters by the time the airframe got to the end as a finished aircraft; such was the commonality of Manchester and Lancaster features. These aircraft became Lancaster I’s. It was easy to pick those Lancasters of Manchester origin because of a line of windows along the fuselage.

W4138 was a Lancaster I manufactured by A.V. Roe at Chadderton in May 1942.

Lancaster I’s on the production line at A.V. Roe. The absence of the line of windows reveals these aircraft to be of the large bulk of Lancaster I’s that had no structural Manchester heritage.

And so was born the best heavy bomber of the Second World War.

A mixture of design genius, a bit of a rebel who would not suffer the indignity of being told to build somebody else’s aircraft and a typical bureaucratic bumble by a committee that did not know what it really wanted until it was presented to them on a plate.

The aircraft pictured is a Lancaster 1 of 83 Squadron in 1942. The letter ‘OL’ signify 83 Squadron and the letter ‘Y’ the individual squadron aircraft. The letter and numbers R5852 were the manufacturers identification and would not change throughout the aircrafts life. The line of windows just along the line of camouflage paint above the wing identify it as one of the Manchester airframes that were turned into Lancasters at the time the Manchester program was abandoned. If an aircraft was damaged she would be removed from the squadron strength, repaired and then re-issued, usually to a different squadron, where the aircraft would be re- identified with the new squadron’s code and individual letter.

This particular Lancaster, R5852, would have been very familiar to Don and he is likely to have flown in it from time to time. It was on squadron strength when Don joined 83 Squadron and was one of the aircraft transferred to 1654 Heavy Conversion Unit with him where it was written off in a landing accident on September 9th 1942.

On “ops”:

Don was posted to 83 Squadron just as the unit finished re-equipping from Manchester’s to Lancaster I’s. He arrived on 17th June 1942 and was assigned to ‘B’ flight, commanded by Sq/Ldr. R Hilton DFC, where he eventually crewed up with a Rhodesian pilot, a couple of RAF types and the rest were a mixture of New Zealanders and Canadians; Don was the only Australian.

Don’s diary mentions raids attacking targets at Duisberg several times, Essen and Saarbrucken but he talks a lot about Ops scrubbed because of bad weather, lots of tennis and cricket. Dances at the NAAFI and girls from the village.

The inclusion of some entries from Don’s diary seem appropriate and they portray a somewhat more complex personality than I expected.

He begins with a poem “O Bacchus” which concludes:

And when at last grim morning dawns

Cool thou my fevered brain

That I may feel as other men

To celebrate again.

17/6/42: Arrived at Scampton and joined 83 Sqdn. “B” flight. Had a late supper, drank beer with a few of the old F/ley (Finningley) lads

22/6/42: Weather sultry. DI (Direct Instruction) on Anson. First flip in Lancaster M (OL-M). Landed at Horsham, drome was small and take off was damned close. Tennis with Huntley after tea and showed a bit of form. Bed early.

83 Squadron Lancaster OL-M taking off on the Bremen raid of 25/26th June 1942. This was the last of the ‘1000’ plan raids

23/6/42: DI on Lanc H (OL-H) Slept in sun all arvo and saw “Weekend in Havana” with Jackson at night. Crewed with Huntley as 1st WOP.

83 Sqn Lancaster OL-H ready for take off on the “1,000” raid on Bremen 25th June 1942 two days after Don did a DI flight aboard her. This was her final flight. Under the command of P/O Farrow RNZAF she was lost killing all on board.

24/6/42: Air-firing from m/u (mid upper turret). Good trip, weather OK. Cleaned guns after lunch- tennis with Huntley after tea and later movie “Virginia”.

27/6/42: Effects of last night not so good. Lecture from OC after Bremen raid. Spoofed for 8 kites and crewed for ops - Scrubbed so went to Lincoln. Had a helluva good night.

30/6/42: DI and wrote Anne in morning. Gunnery lecture in arvo. Circuits and bumps 4.30-6.30.

8/7/42: Usual Sqn duties and some sand shifting. Made 52 for Aus XI in scratchy manner and got 2 wickets.

13/7/42: Right hand u/s after gun accident. Airborn at 6pm, landed Bircotes and F/ley- landed base 8.15. Crewed with S/Ldr Hilton - not happy about it.

18/7/42: Call at 4am, got dressed for flying to find it was scrubbed again, this England! Finally took off for Essen in filthy weather. My first daylight and also first experience of dropping bombs. Went to Lincoln at night but it was foul.

Here Don is showing a considerable talent for understatement.

On this Op Don flew as bomb aimer with B Flight commander, Sq/Ldr. R. Hilton DFC, in Lancaster R5868 (OL-Q) and the history of this famous Lancaster records:

“18 July 42 Daylight raid on Krupps works Essen. Pilot Sq/Ldr. Hilton DFC. Dropped six 1000 pound bombs. 4 hours duration. 10 Lancs, 4 of them from No 83 Squadron, took part; R 5868 was one of only 3 to reach the target; en route two FW 190s were noticed approaching. Hilton received the DSO and P/O. A.F.McQueen, his mid upper gunner the DFC for this raid. Rear gunner was H. Lavey - see logbook copy. His DFM recommendation records that on this occasion he directed evasive action and counter attacks against the attacking FW 190s resulting in R5868 escaping damage.” (4)

The (4) records the Operational flight of R5868 and over the course of the war R5868, as OL-Q (Q-Queenie) with 83 Squadron and later as “S-Sugar” with 467 Squadron, racked up 139 Ops and after the war was put on display as the main exhibit at the RAF museum Hendon.

At this stage of the war it had become common to not crew-up into unbreakable units. Crew members, particularly W/Op, bomb aimers and gunners were held in a pool and allocated an aircraft and a pilot depending on the intensity of Ops, crew injuries and aircraft damage. Pilots, aircraft and aircrew were all in constant flux depending on the operational needs of the squadron.

Don’s diary continues:

20/7/42: Sick parade then stooged all day. Briefed for Rhuhr (sic) raid at 6 pm – Duisberg – airborne at 1130, quiet trip, pranged target and landed 0300.

25/7/42: Hauled over coals for not reporting - bloody liars these Englishmen. Tennis in arvo, opposition weak - later briefing and Ops on Duisberg.

Don again putting laconic understatement on display.

For this operation Don was again crewed with the Commanding Officer of “B” flight, in W5868, as “Q for Queenie” (OL-Q) and again there is a very complete history of the raid because Sq/Ldr. Ray Hilton. DSO. DFC and bar. and the aircraft went on to very illustrious careers.

The detailed history of the aircraft records for this particular raid:

'25/26 Jul 42 Return raid on Duisberg. S/L Hilton. 1x4000lb ‘Cookie’, 6x500 2x250lb. bombs dropped. 3hours 32minutes. Intercepted over the target by an enemy fighter, but escaped unscathed.

The interception report records that at 02.19 at 15,000 feet over Duisberg, the aircraft was intercepted by a single-engine fighter, spotted by the rear gunner 300 yards away. At the same time he and the mid-upper gunner saw two FW 190s 300 yards away to port. The pilot corkscrewed and evaded the fighters. At 02.25 20 miles NW of Duisberg at 14000 feet the mid-upper gunner saw a Bf 110 1000 yards away to port, which closed twice to 5-600 yards and continued closing for another 6 minutes as the pilot took evasive action. No shots were exchanged and the 110 broke away to port. The crew on this occasion included Flight Engineer Sgt Bevan, Navigator P/O Waterbury, front gunner (bomb aimer) Sgt Gilchrist, mid-upper gunner P/O McQueen, rear-gunner Sgt Warren and W/Op F/Sgt Kitto.' (8)

Description of Corkscrew Manoeuvre

For his conduct on this and a previous Operation, on 11th July, 1942, Squadron Leader Hilton was awarded a bar to his DFC.

These photographs record the celebration of R 5868 after completing her 100th Op (left) and (right), her current status as the Bomber Command feature exhibit at the RAF Museum at Hendon.

The diary continues:

28/7/42: NFT (night flying training) at lunchtime, briefing for Hamburg raid at 6pm.

30/7/42: Thurs. Quiet day, briefed for Saarbrucken raid at 1800hrs. Very quiet trip and raid only moderately successful.

8/8/42: Sat. Squadron Conference re 'Pathfinder Squadron'. Town at night and met Margo.

9/8/42: Sun. Off Hilton’s crew and will be first WOP- probable posting to Wyton for Pathfinder. No word from Anne for 4 days.

11.8/42: Not on PF draft. Disappointed.

15/8/42 to 31/8/42: Transferred to Wigsley on 24th - flew transit again. Hell of a hole. Couple of good night ops included in this period but can’t remember dates. The month closes with an early night – feeling very brassed off with life in general.

RAF Wigsley was a typical Class A, Bomber Command airfield. Three concrete surfaced runways surrounded by a perimeter track with 36 'Frying pan' heavy bomber hard standings. Everything was very dispersed and from the Sergeant’s quarters crew had to walk through the village to get to 'Flights' where briefing and kit-up rooms were. In the wet everything got pretty boggy by all reports and it had few features like the older grandiosity of more well-established stations like Scampton where they had come from. Clearly Don was unimpressed calling it a 'hell of a hole'.

The photo above (left) gives the general layout and the photo (right) shows the Control Tower as it is now. In the immortal words of Len Deighton in the afterword to his classic book 'Bomber': 'Only the Control Tower is in anything like its original condition, although if you ascend the iron staircase be careful. You might end up writing a book about it.'

Reading Don’s diary and researching the crews he flew with and the aircraft I was left wondering why he had such a poor opinion of Squadron Leader Hilton. Don had flown with him several times and were it not for Hilton’s bravery and skill his war may have been even shorter than it was. Hilton was a highly decorated pilot and leader and Don had seen him at his best earning the Bar to his DFC on the 25/6th and 18th of July. Don’s diary entry of 4th August 1942 reads: 'General panic for NFT this morning. Hilton acts like a damn schoolboy. Briefed for raid but it was scrubbed later'.

I suspect there may have been a level of sub-conscious envy or frustration. Don had applied for pilot training (amongst other roles) and he had ended up a Sgt. W/Op from the colonies. Don was probably too old for pilot training anyway but I doubt if he was to know that. Hilton was a Grammar School boy from Birmingham who had risen through the ranks of the RAFVR to be commissioned and decorated several times for bravery and leadership, culminating with promotion to the top of his trade as Commanding Officer of an elite operational PFF Squadron. Don was four years older and had lived an independent life including sufficient business success and considerable sporting achievement. I doubt if he was inclined to respond to the sort of clubby discipline that a person of Hilton’s background is likely to have thought appropriate. Don had grown up in a frontier type of environment compared to the big city Grammar School life of Hilton’s early years.

Nevertheless, both Hilton and Don were fighters. Consider Don’s diary of 19th July, just after the previous day’s excitement:

'19.7.42 Damn quiet around here - wish someone would start a war. Tennis with Freddie (perhaps F.H. Huntley, the pilot he ultimately died with) the only activity.'

In many ways, he may have been better of if he had remained with Hilton. Hilton went on to complete his second Tour and Don might have finished his first if he had stayed.

Although it would not have done to stay too long. When Hilton came back to active service after a staff job at the end of his second Tour he was awarded the DSO and made Commanding Officer of 83 Squadron. On the 23/24th November 1943, on his third Tour, in the early missions of the cataclysmic 'Battle of Berlin', Wing Commander R. Hilton DSO, DFC & Bar, flying Lancaster 3 (JB284), Code OL-C, was attacked by anti-aircraft artillery and shot down and killed, along with all of his crew, while on the bombing run.

Back at Scampton:

We need to turn our attention back in time to Scampton, where, with 83 Squadron in August 1942, there were major developments. The Pathfinder Force idea was getting organized and 83 was one of the founding squadrons, but only the most experienced crews were to go with them. Don was very disappointed not to be selected but he had been there less than 2 months even though he was dead keen to get into the fight.

The senior crews at 83 Squadron moved to RAF Wyton which was to be the PFF base. 57 Squadron RAF moved in during September 1942 and were joined by 617 squadron in March 1943. 617 was a special Squadron formed from the most experienced volunteer crews from across Bomber Command tasked initially with the 'Dams' raid, Operation Chastise.

The un-drafted members of 83 Sqn were re-mustered to a new unit called 1654 Heavy Conversion Unit (HCU) at nearby RAF Wigsley, a satellite field for RAF Swinderby, which was formed from crews left over from other squadrons involved in the formation of Pathfinders. At that time being in a Conversion Unit did not exclude crews from going on Ops. Crews at HCUs were typically experienced aircrew, with a couple of extras to make up the standard complement of seven for a Lancaster, converting from medium bombers like the Wellington, Hampden and obsolete Whitleys to the new ‘heavys’ or from Stirling and Halifax squadrons as Lancaster numbers built up. They often had extensive battle experience in their earlier types. HCUs are perhaps best thought of as operational reserve squadrons whose crews were ready to be posted to regular squadrons as combat losses occurred. Up until September 18th 1942 it was even common for crews in OTUs to fly on Ops and this was noticeable when Bomber Command started putting on Ops calling for ‘Maximum Effort’; like the '1000 bomber raid' starting with Cologne in May 1942.

For the new crews at 83 squadron in June 1942 much time was taken up with Direct Instruction (DI) training which was essentially ‘learning by doing’ and might involve low level practice, practice forming the stream, night flying training, gunnery and bombing practice. The other activity was called 'Spoofing', a piece of RAF slang, and it is hard to get a precise definition of it. Typically Spoofing was involved when a group of aircraft would mount a dummy raid to divide the defences or to try to mislead the defenders as to the identity of the real target. Apart from flak ships and night fighters over the North Sea there was little time spent in fully hostile airspace. Leaflet propaganda drops could also be involved but such operations did not count toward a ‘Tour’ of duty, which was 30 Ops.

The diary does not take up events after 31st August, about a week after Don and his crew went to join 1654 HCU. Don’s diary mentions several Ops between 15th and 31st August but he does not specify dates or targets.

Night-fighter defences:

Bomber designers, and aircraft designers in general are always in a bind. The airframe can carry only so much and the choice has to be made. Do we carry defensive armament and the crew to operate them or do we carry bombs? Do we carry more of anything at a lower altitude where they are more vulnerable, or carry less at a safer altitude? The British made their choices and the Americans theirs.

If there could be said that there was a design deficiency in the Lancaster it was in the lack of defensive armament or at least an observer scrutinising the airspace below and behind. This is where most attacks came from and the German night fighters capitalised on that weakness (in all Bomber Command heavies).

The general pattern of Luftwaffe night-fighter air defence relied on a complex radar network. A long range Freya radar near the Dutch coast would pick up the bomber stream forming over England and, when they came in range, would guide a short-range Wurzburg radar to the bombers stream which in turn would pick out an individual bomber. Each Wurzburg was assigned a 'Box' of airspace and each Freya would be dealing with a certain number of Wurzburgs. Assigned to each Wurzburg were night fighters each equipped with Liechtenstein airborne interception radar and the Wurzburg would guide a nightfighter to within range of the Liechtenstein.

The fighter would approach, in radar contact, from below and behind until an identification was made and the fighter would typically position himself almost directly below and slightly to port of the bomber. When in position the fighter would pull up almost into a stall and direct a full broadside of no-deflection cannon fire into the port wing root of the bomber where the main fuel tanks were. With no warning whatsoever all hell would break loose on the doomed bomber and the fighter would stall away under the recoil of the heavy gunfire, recover and start the hunt for the next target, guided by the Wurzburg. Some of the top Nazi pilots could bring down 5 heavy bombers in one night. Eventually in 1943 the Germans fitted 2 forward and upward firing 20mm cannon behind the cockpit. This further simplified the attack from quarters that the bomber had no way of observing. This was given the deceptively benign name 'Schräge Musik', literally Jazz, or Strange Music.

In general, the German night-fighters were primarily armed with 20 and 30mm cannon and while these guns were relatively slow-firing and limited in range they were devastatingly effective at the range of a typical interception in the night-fighter role. Single-engine fighters were never used really effectively as night-fighters by any combatants during the war and the twin-engine Messerschmitt Bf 110G and the Junkers Ju 88G armed with cannon were ideally suited to this role. In a typical attack in the hands of an experienced pilot a heavy bomber stood little chance. Many Bomber Command aircraft were lost without ever knowing where the attack came from.

Final flight:

When Don and his crew flying W4138 (code JF-U) took off from RAF Wigsley on the evening of September 16th Don was on his 11th Operation. The brains trust of a Lancaster were: the pilot, engineer, navigator and wireless operator and they were all clustered together underneath the Lanc’s characteristic plexiglass cockpit cover. The pilot on the left and on his right hand the engineer on a little fold down seat. Flying the Lanc was a full time job for the pilot and the engineer did all mechanical adjustments to keep the Merlins running sweetly, generally looking after the mechanicals while the pilot concentrated on flying. Seated lower, directly behind the engineer, in an alcove that was curtained off, was the navigator facing outboard to port and immediately astern of him was the W/Op station, just in front of the main spar, facing forward.

The crew of W 4138 on this fateful mission were:

Pilot. Sgt. F.H.Huntley. RAFVR. Flight Engineer. Sgt. R.A.Low. RAF. Navigator. Sgt. L.E.Bell. RNZAF. Bomb Aimer. Sgt. J.N.S.King. RCAF. Wireless Operator. Sgt D.R.Gilchrist. RAAF. M/Upper Gunner. Sgt. S.H.Cowley. RCAF. Rear Gunner. Sgt. M.R.Crocker. RCAF.

Seven men and an aircraft all with a common purpose. The Lancaster to carry the load, a bomb-aimer to put that load in the right place. The pilot and flight engineer to control the aircraft and keep it in the air. Navigator and wireless-operator to get the aircraft to the right place to a tolerance of a few hundred yards over blacked-out, hostile Germany; when paradoxically, the weather conditions that were most help to their survival were the least conducive to the success of them being there in the first place. The gunners were the aircraft’s eyes straining in the darkness for threats to them all.

The target for September 16/17th was Essen, the main industrial city of the Ruhr and after take off at about 2015h Lancaster W4138 joined the main Bomber stream and headed out over the North Sea

A Lancaster 1 of 44 Squadron flying low over Lincolnshire in April 1942.

The Ruhr Valley was the centre of German heavy industry and known apocryphally as 'Happy Valley' to bomber aircrews and, aside from Berlin, Essen was the best-defended target in Germany and aircrew losses had always been disproportionately high in the many air battles fought over the Ruhr. The chances of survival for Bomber Command aircrew were not very good. A 'Tour' was 30 Ops and losses were between 4% and 10% per Operation. If you do the arithmetic; in 1942, to out-live the war was a statistical impossibility. Lucky individuals did of course, such is the nature of statistics, but you would not bet on it. Crews were at greater risk on their first 5 Ops and then the odds improved somewhat with skill and experience but basically, after a crew had survived about 7 Ops they were then living on borrowed time.

Left: Cockpit of a Lancaster.

Looking down into the nose through the little corridor is the front gunner/bomb aimer’s station. The engineer’s seat folded up to the right. The only armour on a Lancaster was underneath and behind the pilot’s seat. There was no co-pilot and in the result of incapacity of the pilot it was assumed that the Flight Engineer would be able to take the controls.

The first of the 'Thousand Bomber Raids' was held in late May 1942 and as June progressed the defences became steadily more organised in the face of large numbers of aircraft attacking one target. The first over Cologne had relatively modest losses of about 3.8%. There were only 3 such raids because mustering the 1000 aircraft was severely depleting the OTUs and the tactics were not yet up to getting that number of aircraft reliably over an accurately market target. When OTU crews were used there were usually several senior instructors heading up a number of only partially trained crew members. These crews were flying aircraft which were not the latest variants, well past their prime and consequently suffered disproportionately high losses. Losing irreplaceable senior instructors was the Achilles heel and the ‘1000’ plan was discontinued. By the time of the large raid on Essen in September 1942 Bomber Command had reverted to the “Maximum Effort” concept which only used available aircraft and crews from operational squadrons and trained crews from the Heavy Conversion Units. For the Essen raid the weather was good but the defences were ready. Of the 389 bombers attacking Essen on 16/17th September, 41 aircraft (10.5%) are listed in official RAF records as being lost.

Despite the unusually high losses, Bomber Command War Diaries record the Essen raid of 16/17th September 1942 as being a very effective raid, which was in contrast to the rather ineffectual efforts that preceded it. Perhaps the good weather in mid-September 1942 was ironically favourable to both the success of the raid and the defences.

The tactics that led to the general improvement in results on the target were a mixture of dedicated target marking aircraft (PFF), rapidly evolving electronic navigational aids, like Oboe and H2S and 'Bomber' Harris’s idea of concentrating large numbers of attacking aircraft over the target in a short period of time to overwhelm the defences. But those results came with a cost and 1942 was still very early in the fight.

The simple fact that the combined land forces of the Allies were simply nowhere near strong enough to consider a landing in Europe within the next 18 months at least meant the only way to prosecute the fight against Nazi Germany in the west was from the air for the foreseeable future. So the allies had no option but to persevere. The heavier load capacity of the RAF was used at night and the higher altitude, more precision effort of the USA’s 8th Army Air Force during daylight. Losses for the USAAF and the RAF continued to be high all the way through until late 1944 when the Nazi war machine began to falter under continual attack. Until then there was minimal expectation amongst aircrews of surviving long enough to finish a tour of operations.

The Lancaster was a comparatively difficult aircraft to escape from, when coming down after it had been damaged beyond hope in an attack by German defences and it was typical that if a heavy bomber was shot down during a raid then all the crew died together.

In a Lancaster the escape hatches were slightly smaller than those on the other major heavy bombers like the Halifax, The Halifax interior was much easier to move around in but to do this required the bomb bay to be much shallower which in turn restricted the bomb load, the Halifax carried 4,000lb less bombs than a Lancaster, smaller bombs only, was 30 mph slower and flew 3000 feet lower operationally. In 1943 one source reported the average operational life of a Halifax was 13.9 operations delivering a life total of 22.3 tons of bombs; whereas for a Lancaster the life was 19.4 operations delivering 76.6 tons. The Halifax was less manoeuvrable but more comfortable and Harris, obviously using different sources, thought little of the type, writing in late 1943:

'For every Lancaster lost on operations, 68.5 tons of bombs are dropped. Corresponding figures for other types are 30.1 tons for the Halifax and 21.6 tons for the Wellington. Again, for every 100 tons of bombs dropped by the Lancaster, nine aircrew .. are killed or missing. For other types the figures are Halifax 19, Wellington 23. Finally, the advantage which the Lancaster enjoys in height and range enables it to attack with success targets which other types cannot tackle except on suicide terms.'.

Is it any wonder that Harris wanted Lancasters and more Lancasters.

W4138 crashed near the village of Willich, 8km SSE of Krefeld in the Ruhr Valley, and of the 7 man crew, 5 were found with the wreckage. Don’s body was not amongst them. At first it was hoped that he had survived and contacted the Resistance who were increasingly effective at getting aircrew who had successfully baled out and avoided capture back to the UK via Spain. This was not to be. He was reported dead by the Red Cross some days later so we can conclude that he probably baled out after the aircraft was hit and already coming down. We can further surmise that W4138 had bombed the target and was on the way back to England when it was shot down. RAF records are that she was shot down by a night fighter the activity of which was very high in that area in particular and even in 1942 the radar direction of the air defences was highly organised and all night fighter units were equipped with Liechtenstein interception radars by mid 1942.

Left: Messerschmitt Bf 110 G night fighters with Liechtenstein radar and under-mounted cannon of the sort operational in the defense of the Ruhr valley in September 1942.

The assumption that W4138 had bombed the target before she was shot down is allowed because the wreckage and the bodies of the crew with her were identified at the crash site. If a fully bombed-up Lancaster, full of high-octane fuel and 14,000 lb. of high explosive was flown into the ground it did not usually leave much to identify.

It was a simple fact that few aircrew managed to bale out if their aircraft was brought down during a raid. And those that did faced many threats beside being apprehended on the ground. The aircrew were called 'terror flyers' by the people being attacked and civil defence personnel on the ground had few compunctions about killing them on the spot.

My best guess is that Don baled out of the stricken Lancaster on the way back from the target in the early morning of September 17th 1942 and died of wounds, or his landing, or was perhaps killed on the ground trying to evade capture.

Whatever happened that night, Don was buried with the rest of the crew, initially at Krefeld-Bochum, quite near where W4138 came down, and later moved to Reichswald Forest War Cemetery at Kleve, Nordhein-Westphalen.

Of a total of 7,377 Lancasters built, more than half were operational losses and only 7 percent of the crews of shot down Lancasters survived. W4138 had a total of only 41.25 flying hours when she was lost with all of her crew.

When Sir Arthur Harris was made chief of Bomber Command in February 1942 he came with a plan. That plan ignored the British experience with the 'Blitz' in which the indiscriminate bombing of areas of population (instead of precise targeting of military targets) failed to cause demoralised disintegration of the population and thus its ability to conduct modern warfare. Harris considered that the London Blitz was the right plan, just not pursued in an adequate manner. Bombers not big enough, not enough of them, and not used for anything like long enough or followed through with enough vigour. The only legitimate target for a bomber was the triumvirate of: civilian worker population, the Military/Industrial complex and the Military itself.

To Harris they were all the same.

To get the USA into the war in Europe Churchill had to keep Britain in the fight. In 1940 the only way for the Brits and eventually the Allies to do that was in the air. And even then only at night did Bomber Command have losses at a level that could be sustained by the supply of new aircraft and trained crews. So in early 1942, in Churchill, Harris had the right man at the top pulling the levers.

Not that they always agreed. Harris subscribed to the Douhet philosophy that 'The bomber would always get through' and the 'Total War' concept that made the civilian industrial workforce a legitimate target. Harris believed that ‘Area Bombing’ alone, utilising massed heavy bombers and unrelenting force would drive Germany to the negotiating table. Churchill, on the other hand, believed that the war in Europe would eventually be won by infantry on the ground holding rifles.

History shows that Churchill was right and Harris was wrong. The RAF war came to a climactic denouement with 'The Battle of Berlin' starting in late November 1943, lasting until late March 1944, when Bomber Command was brought to its knees by crippling losses and had to admit defeat. Like the last bridge at Arnhem in late September 1944, Berlin in late ’43 was a city too far. For the crews of Bomber Command it was a 9 hour slog over fully hostile airspace and in late 1943 the Luftwaffe still had plenty of sting. By March 1944 Bomber Command has to admit that it was not able to expand to the whole of the Reich the shocking effect that the raids on Hamburg between 24/25 July and 2/3 August 1943, suitably named Operation Gomorrah, had produced.

The area bombing strategy never reached the same intensity again and by 1945 Lancasters were used much more in support of the allied land war that began in Normandy in July 1944 attacking tactical military targets rather than general industrial ones.